Bitcoins and Gravy Episode #55: BitTunes : Setting Music Free! (Transcript)

Episode notes and comments page :

https://letstalkbitcoin.com/blog/post/episode-55-bittunes-setting-music-free

Professional transcription provided by a fan and consultant of the show, who can be found at :http://www.diaryofafreelancetranscriptionist.com

John Barrett (announcer) : Welcome to “Bitcoins and Gravy”, Episode 55… Five, five, double nickel..”Five, five…anybody?... Anybody? …Five, five… Anybody?... Five, five… Sold!”

At the time of this recording Bitcoins are trading at $244 each, and everybody’s favourite, LTBCoins, are trading at $0.000234 U.S. dollars. Mmm…Mmm…Mmm… Now that’s gravy.

[intro music]

John : Welcome to Bitcoins and Gravy, and thanks for joining me today, as I podcast from East Nashville, Tennessee, with my trusty Siberian Husky, Maxwell, by my side. Say, “Hello.”, Maxwell.

Maxwell : Grrr…

John : We’re two Bitcoin enthusiasts who love taking about Bitcoins, and traveling the globe in search of interesting and compelling information about Bitcoin, and about all things related, here at the dawn of the “Age of Crypto-currencies”. Thank you for being here, once again. New listeners, welcome to the show.

John : On today’s show I travel “down under”, to Adelaide, Australia, to speak with Simon Edhouse (https://au.linkedin.com/in/simonedhouse ), the CEO of BitTunes ( http://www.bittunes.com/ ). Bittunes is reinventing global music distribution, by creating a people-powered platform. Simon talks to us about how this platform allows “P2P”- that’s “peer to peer” - file sharing, to achieve its full potential as the optimal internet distribution mechanism, and how he aims to monetize the exchange of digital data. By the way, Simon is a man of conscience, who has been following the legacy of his family in working for the greater good. It’s not just about making money, folks. Sometimes it really is about doing what is right for humanity.

[Segway music]

John : All right. Ladies and gentlemen, today on the show I am thrilled to welcome Simon Edhouse. Simon has a background in music, having played in bands in the ‘80s and ‘90s. He’s also an award-winning songwriter and composer. He has a background in film and video production, holography, and advertising - as an ex-“Ogilvy and Mather” managing director in Shanghai. After returning from China, he did a master’s degree in Science and Technology Commercialization, writing his thesis on future uses of digital currencies, in 2006. And, of course, Simon is the CEO of BitTunes… BitTunes, “Creating a People-Powered Platform to Reinvent Global Music Distribution”. At the moment, he is based in Australia, but he is planning a move to London. Simon, welcome to “Bitcoins and Gravy ”.

Simon : Thank you for the nice introduction. Yeah, BitTunes is my main thing that I’ve been involved in for a while. But to go back to what you were saying, the thesis I wrote in 2006 was, at the time, considered very, very left-field. I mean, the lecturers that I has just thought I was crazy, because they said that, “This is completely hypothetical.” And I had a lot of trouble with them because of that. But for me, I’d been witnessing what’s been happening with peer-to-peer for a couple of years. Firstly, there was Napster, and then there was the plethora of, kind of, new music P2P applications. Then right in the middle of that thesis, along came Skype, and that was so clearly a very influential thing, because up to that point peer-to-peer had been, kind of, stigmatized because it had been associated with piracy. But then along comes Skype, and Skype says basically, “We’re going to completely change the telecommunications industry. Sue us if you can, but you can’t, because we’re not doing anything illegal.”

John : Right.

Simon : That was really interesting for me, because peer-to-peer, I’d already realized, was very powerful technology. But it doesn’t have to be associated with anything illegal.

John : Right. Exactly. I think a lot of people still don’t know that, but you know, we’re still at the very beginning, so it’s understandable that a lot of people don’t understand that.

Simon : Yeah, that’s right. Yeah. But having said that, one of the interesting things I often point out is, I differentiate what I call “internet technology” with “web technology”. The short way of saying it is, “The internet is not the web, and the web is not the internet.” And the way to look at that is, the internet is twice as old as the web. The web is like an overlay that happened on top of TCP/IP , which is the transfer protocol of the internet. Now, all of the peer-to-peer applications sit on top of the transfer protocol TCP/IP. But then, around the very late ’80, early ‘90s, came the web. The web is just really – if you can visualize it - it’s just the domain name system – the DNS system – and the browsers. You know, Internet Explorer – well, first there was Mosaic, then there was Netscape, then the dominance of Internet Explorer. Then we had, of course, Safari and Firefox and Chrome. Now most people think that is the internet, but really this is an overlay on top of the internet, called “the web”. And Skype is not the web. Skype is an application that sits on TCP/IP. It’s a P2P application. Same with a lot of the “file sharing” applications. They’re not web sites. [The} simple way of looking at it [is] they need a browser basically. But what I reasoned back then – and this was before the iPhone, before the App Store, [and] before people were thinking about applications. It was more a time when the fashionable concept was “software as a service”. You had sites like http://www.salesforce.com coming in and taking the management of people’s accounts, and businesses, and putting it onto a web service. And that was the, kind of, rage of the day. But what happened when Apple, particularly, launched the iPhone, and then out came the App Store, it was a shift, then, towards applications again.

Now, prior to that, applications were P2P applications, or, etc. So what I reasoned back then was the future had to be an application-based future. And a simple way of looking at that is, that is where the people are empowered, because the application happens on your device. If you’re using Salesforce.com, or a web service, the application is sitting on the server, and you’re a client. You’re “sucking on the dummy”, you know, from this service that’s coming down from a central point. When you’ve got applications on your computer, you’re in control of the application. And when they get really dangerous – as it were – to the mainstream system, is when those applications start talking to each other, and don’t need central control. That’s when it gets fun. Skype is partially that kind of application, although they have some centrality. But these kind of applications that empower end-users, that really seem to me to inevitable, really seem to me to be inevitable. And, of course, I looked at what you could do with applications like that, and one of the first and biggest things I thought, “Gee, wouldn’t it be great if we could just have a peer-to-peer application that exchanged money. So we started to think about how that would come about, and what would be involved, etc. And I wrote my thesis really on saying, “This is inevitable, and so when it comes, what are we going to do with it?” And basically, one of the major things I thought of doing is doing an independent music market, that redefined how music was distributed, but in a legal way so that we could never be sued by the record industry association.

John : These days, when people ask me, “What’s the point of Bitcoin? I don’t understand this. What’s the point of crypto-currencies? We have money. We have credit cards, and all of that.” I say, “Listen, I can send, across the country, to you a photograph. I can send you a short film. I can send you some music. I can send you all of these things for free. Why can’t I send you five dollars as a tip on your birthday, to say, “Hey. Go get a pint of beer. It’s on me. Why do I have to pay for that?” And every time I ask somebody that question, it stumps them. They say, “Well, what do you mean you have to pay?” “Well, there’s always a third party. I can’t just send that to you.” And they don’t have an answer. They don’t understand it. And I say, “Well, the reason is that there are these third parties out there that want to get a cut of it.” Right?

Simon : Yeah.

John : And so, Bitcoin is basically saying that we want to set up something that allows people to send a photo and five dollars at the same time, and it only costs a couple of cents. No big deal. Nobody has to sweat over it. The $5 is probably not an attempt by a terrorist to launder money, right?

So you have obviously an interest in Bitcoin the protocol, but I have a quote from you. You said, “We’re not interested in making a profit from Bitcoin . We’re interested in distribution of value to end-users”. And I loved that. I got that off of a video that I watched of you speaking.

Simon : Okay. So, just rewind a little bit, to what you were talking about about the value you saw in Bitcoin, and that is in sending $5. I mean, let’s make an analogy to that as saying, in the old days you wrote a letter, and then that letter you put it in the post box, but you needed the postal service to get that letter from point A to point B. But now you send an email. Okay, now the email is far more direct, and gives you the control that you can bypass the postal service. And, of course, an order of magnitude less postal items are being sent now than before, because this new technology has come. But Bitcoin is really just like a $5 note. I walk down the street, and I give you a $5 note for something, and you say, “Okay, thanks.” That’s what Bitcoin is. It’s just a direct exchange of something, without having to go through multiple systems. It’s just digital cash. But like everything, when something is new, people look to the current system and they say, “Look, if it ain’t broken, why fix it?” Well, you know, I don’t really want to get into an argument about why the current system is broken, because it’s pointless. You either see that it can be improved, or you don’t. If you don’t, I’m not going to try and convince you. What I tend to lean towards is to say, “What can digital currencies do that current monetary systems cannot do?” And then, you’re going to win the argument. And that’s what’s happened in the ecosystem, too. It’s things like remittances. Remittances are very expensive for the poorest people in the world. If they can move towards a Bitcoin remittance model, they’re going to save a lot. So things like that are no-brainers. But BitTunes is about taking the model further. In a peer-to-peer application you have digital bits and bytes of data that are going here and there. And what occurred to me very early on is, if you’ve got digital bits and bytes of data of an mp3, or music file, or whatever – going from “point A” to “point B”. In actual fact it’s usually from a cluster of providers to one requester. So there’s a number of people providing to one new requesting person.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : But because it’s all digital, and because it breaks up into tiny little proportions, why can’t we just match digital for digital? In the sense that the digital money – which can be divided, as you know, a Bitcoin can be divided into a hundred million pieces. You just measure the amount of digital data that’s going between these users on the internet, and then you reward them exactly in the amount proportionate to the amount they provided to the requesting user, in digital money. Now, you just can’t do that with conventional money, because you’ve got to have banks involved, and you’ve got third parties, and you’ve got random clusters of people – on the fly – being called on to provide a file to a new requesting user. And that assembly of those five or six providing users to the new requesting user is convened in just a few split seconds, and then the provision of that file is over in about a minute.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : So, how can you organize that through Paypal [laughter]? Or through Mastercard? You can’t.

John : No.

Simon : These are the kind of things that Bitcoin is absolutely suited for, and real money – that people use everyday – is absolutely not suited for.

John : Yeah. Nicely explained. Thank you. That was great.

Simon : It’s the things that Bitcoin can do - that other monetary systems can’t do - that are the no-brainers to actually start to explore. One of the problems in the Bitcoin ecosystem is that you’ve got a lot of people who are trying to take the easy route. You know, they say, “Well, we can replace banks.”… blah… blah… blah. They’re going to find a lot of resistance to that.

[laughter]

John : You think so?

Simon : I think so. From the bankers, for a start.

John : Absolutely. Yeah. You know, I love the optimism, though, in the Bitcoin world – especially among the younger people. I’m 51 years old – oh wait! Did my listeners know that prior to this moment?... I think they did… Anyway, yeah, I’m 51, but when I was 20 years old I also hoped for a revolution, and all of this. And I still hope for a revolution of sorts, but I think just in the same way that we’ve had this slow, downward spiral into decay – in so many ways that we’ve seen in our country, the United States, in my opinion. I think it’s going to be just as slow for us to fight the uphill battle to get back to level ground, where we are being treated fairly again, and where the power is back in the hands of the people. I don’t think it’s going to happen overnight with Bitcoin – we take over the banks, we take over the government…

Simon : No.

John : … And we’ve won the revolution…. in just a couple of short months, or a couple of short years. It’s not going to be that way.

Simon : No.

John : And for some reason, the powers that be in this world always have – I guess it’s because they’ve been corrupted by power – they have this strong desire to subjugate people. I don’t know what it is. It’s the animal, right? It’s the Alpha dog. It’s the something. I don’t know what it is. So, we have the good fight to fight, until the end of time I’m sure.

Simon : Yeah. So the message is, “Fight battles where there’s no opponent.” I mean, if you’re trying to take on the banks, well then you’ve got a huge adversary there. And not only in the banks themselves, but all of the people who are quite comfortable using the banking system, who will argue until they’re black and blue in the face that, “Oh, well why change a system that isn’t broken”…blah…blah…blah. Why not do things with digital currencies where there is no analogue in the real world. You know, there is no “other thing” that can do that particular function. So therefore, you’ve got clear air.

John : Hmm. Yeah, I like it.

Simon : Being a startup trying to work with new technology is hard enough. It’s hard enough with all of the challenges, and trying to convince people of new things. But if you know that you’re onto something that is like a no-brainer – because it’s just so obvious – well, just hang onto it, because eventually people will come around.

John : I agree. Now before we get into BitTunes, I have a question. I’m really curious about this. When it comes to micro-transactions, because we believe that that could be the future for the internet, right? Somebody writes an article, and you tip them. They’re already doing it with ChangeTip (https://www.changetip.com/ ), you know? They’re already doing this. So, you want to tip somebody 5 cents – you know, for my show. Sometimes someone will tip me, and it’s $1.25. That’s great. I really appreciate it. But as far as these micropayments, and these micro-transactions, who fears that? We know that the governments fear the money laundering, and I can appreciate that, because we don’t want terrorists or organized crime to do money laundering – even though it’s rampant on Wall Street [laughter], you know? As far as the micro-transactions, and the micro-tipping of 50 cents, or 5 cents, or whatever. Who is against that? Do you have any idea? Who fears that? Do banks fear that? Is it impossible to regulate?

Simon : I guess, for me also, there’s a very important point about micro-transactions, and it’s one that I feel that most people are just, again, not thinking about. In the Bitcoin space, almost all talk of micro-transactions, is about users paying the micro-transaction to business. And now, in ChangeTip you can tip somebody else. But what about the reverse – which is what BitTunes is - which is business organizing payment of micro-transactions to end users. So the flow is happening the opposite way. Most people think about micro-transactions as another way to do, say for instance, a paywall where you can go to a web site – it’s a newspaper site – but rather than pay a monthly subscription, you’re paying some “X” amount of Satoshi for every page that you turn.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : So it’s just at a very small level, and it doesn’t influence you much. But where is the flow going. The flow is going from the poor users – who I tend to be on the side of - toward Rupert Murdoch.

John : Right.

Simon : Do we need it to go in that direction? What about the other direction? What about businesses providing micro-payments down to end users, for the things that end-users are doing? Now what do end users do this is of value? How about distributing music? You know? So it’s a completely opposite way of looking at micro-transactions. But almost nobody is focusing on that because, like I said, in a startup often things are hard enough, so entrepreneurs often tend to go for the low-hanging fruit. “Let’s just do something that’s existing in the marketplace, and we can find a better way to do it with Bitcoin .” So in my mind, I separate these into, what I call it, “Type 1” and “Type 2”. Type 1 micro-transaction is payments to business from “punters” – from the ordinary people. Type 2 is going the other direction. So your question is, “Who’s threatened?” Well, so if we’re talking about Type 1, which is payments from end users to business, well I guess it’s the people who are providing paywall systems, and people who are providing that type of function. Now, it’s not like that is, in any way, a large slice of the banking industry, or PayPal, or some of those larger legacy players. So it’s not really eating their lunch at the moment, mind you I think that if it’s going to be a large thing they want to be involved. But if it’s the reverse - if it’s payment from business towards consumers, yeah there’s even less people thinking about that. So that’s why, again, we’re doing it, because it’s wide open, you know? I tend to try and look for things where there’s a lot of blue sky.

John : Nice. I like that. Now, of course, there are entities out there that BitTunes potentially threatens – models that it threatens, right?

Simon : Oh, yeah. I mean, I think they would look at us and just think that we resemble a few molecules on the back of a flea on the back of an elephant. You know? I mean, we’re insignificant. In fact, it’s true. We are so small, compared to the legacy players in the ecosystem. Also, there’s been a pretty dramatic shift in the way people are thinking – in the industry – about music, in the last ten years. Because what’s happened, really, is - even eight to ten years ago – everyone was still really worried about file sharing and music downloads. But now you ask industry aficionados, and they’re just saying, “Downloads are dead.” Because of streaming. So it’s the streaming music applications which are the huge, and growing, phenomenon.

John : Right.

Simon : But you survey 100 medium-level artists, I don’t think they’re going to be that enamoured with the streaming model, because it’s got a lot of problems in relation to remuneration to artists. They pay very poor royalties. Coming from an artist background myself, I just look at streaming and I think, “Well, yeah I want to take you down. I don’t like this, but it’s really, truly a David and Goliath struggle.” You’ve got to think about the long term, and think, “Well what makes sense? Does it really make sense for no one to own any music?” I mean, it’s a ridiculous argument, but I sometimes feel like saying to people is, “What happens when the Zombie Apocalypse” happens, and all of the streaming music services go offline? Noon has any music anymore? So music is dead?” You know? I mean, I’m not serious. But a lot of people talk about the apocalypse. Well, what about a Kickstarter project where you have solar powered mp3 players, and you make sure that you’ve got 10,000 of your favourite songs, that even when the electricity grid goes down, you can still listen to them powered by solar.

John : Nice.

Simon : It’s a ridiculous argument, kind of. But then, who knows, you know? [laughter] But what I man is, do we really want to have a world where we’re sucking on the nipple of some music provider who’s telling us what we want to listen to. And if that was to go offline - for whatever reason, a nuclear war or God knows what – BANG!, the music gets shut down. And who has music anymore? It doesn’t make sense to me. I mean, would we have had “The Beatles”? Would we have had “The Sex Pistols” If that had been the order of the day? Would we have had “Nirvana”? Would we have had these breakthrough moments in music. If you can imagine, look back at the last 30 years of music. Music chugs along, and you have eras – like during the ‘70s, you had the “disco” era, and everything is the same, everything is the same, everything is the same. All of a sudden, “punk” music comes along…Bang! Everything changes. And in the ‘90s, Nirvana came along, and it just went – Bang! Everything changes. Now, what’s going on with the kind of effect that Spotify (https://www.spotify.com ) and Pandora (http://www.pandora.com ) have on the market? There are guys in the music industry who just look at the chord structures and tempo of music that’s popular at different seasons of the year, and they just keep pumping out the same kind of music. So, is there going to be a Nirvana that’s going to pop out of Spotify? I somehow doubt it.

John : Yeah, yeah. Well, the same thing happens in Nashville. We’re very critical here – some of us - about the cookie-cutter music industry - with “new country”, as they call it – that’s replacing the “old country”, I suppose.

Simon : Yeah. It comes down to this word called “curated”, when you have curated music services by a centralized group of people who think what’s the best music for you. Or then you have – I give credit to Spotify (https://www.spotify.com ), in the sense that there’s not a bunch of guys there in Finland who are saying, “You should listen to this music.” They’re looking at the patterns of music that are being listened to, and trying to match people with, kind of what’s called, “collaborative filtering”. You see what this group of users are listening to, and then you try and match those users, and “If those guys over there like this music, then maybe this guy – who’s a bit similar – will probably like the same music.” But that tends to homogenize everything, as well.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : But, let’s get into the hypothetical future scenario, and the one that I tend to always believe is possible. And that is, we’ve all got intelligent devices in our pockets – called iPhones, or Android phones – and these things are much more powerful than the computers that helped us land on the moon. Or much more powerful than even servers were 10 or 15 years ago. We’ve got very smart devices in our pockets. Now, are these just “slave devices” that take their feed from higher above, and then play this or play that? Or are these devices capable of being intelligent, in terms of talking to other devices independently, and curating by the wisdom of the crowd, to each other in a way that has no semblance of centrality?

John : Mmm..Hmm.

Simon : That’s what I’m interested in. What I’m interested in is putting the data sorting processes and recommendation right down in the user’s pocket, and getting the hell out of that as a business. I don’t want to be in that. I want users to be totally in control of that. And you know what? For business, that’s kind of anathema. Most businesses who are involved in this area would just look at that concept and go, “Whoa…whoa…whoa! No we can’t have that. We can’t have the users in control.”

John : Right.

Simon : My thesis, in 2006, basically came up with the final conclusion of, “How do you make an internet business where you let go of almost all control, but still maintain just enough control to make a good business model, but you’ve got to give away a lot of control to the users?” And curation – “wisdom of the crowd curation” – powered by all the users, would therefore be privacy protected. All of the interest data of those users can’t be monetized by Facebook or Google, because it’s not available to them. That’s what’s exciting.

John : I like that. And to go from that into your mission statement, I think is appropriate. It says, “To create a platform that allows P2P - that’s peer-to-peer file sharing - to achieve its full potential as the optimal internet distribution mechanism. And to do so by monetizing the exchange of digital data.” I love that. So maybe you can walk us through an example of how BitTunes would work.

Simon : I guess my mind immediately just goes to the fact that you’ve got this file, and it’s requested by somebody, and those people over there have that file. Well, they start providing pieces of that file to the new requesting user, because they each have the same file, and that file just gets hashed into little, tiny blocks. And everyone starts providing, you know, block one…two…three…four…five…six – in various order, until the requesting user has all of the blocks. Then all the blocks filter in until that requesting user has all of the blocks necessary to make up the mp3 – or the digital file. Then bingo! He’s got it. Now each of those tiny pieces were provided by those people. They get rewarded for what they provided. To me, I’ve been talking about this model for a while, so it’s fairly straight-forward. But the thing about peer-to-peer technology is that there’s all these other wonderful things you can do with it. Like the idea I was talking a minute ago about, the end game plan for BitTunes is the embedding of songs – the ownership of songs – in a blockchain, that protects the rights of the producer of the song. In other words, it’s a, kind of, certified copyright system in a sense that, even though copyright has a lot of baggage. And a lot of people who are in the, kind of, piracy, “anti-copyright left”, they don’t like the idea of copyright. But let’s grab 100 musicians and say to them, “What do you think of copyright?” Well, they want the rights of the song they’ve written to be certified somehow.

John : Sure.

Simon : They’re all very interested in having that. Now, do we want that being in walled gardens of rights organizations all around the planet, who charge artists for that? Or can we put all of that in a blockchain? You absolutely can put it in a blockchain. So putting the song ownership in a block chain – let’s call that “Tier 1”. Now “Tier 2”, sitting above that, is the transactions in relation to the ownership of that song? Who bought it? When? And all of that kind of transaction and purchase data. Now that, again, can be put into a blockchain. Look, blockchains are very good at some things, and they’re not very good at others things. But one of the things blockchains are quite good at is being able to map the transactions - between entities - of something. So, “Something was sold to this person, and then sold to that person, and this person was involved, and that person…” A blockchain can do that very well. So, Tier 1 is the ownership of songs. Tier 2 is the transaction history of music. Well, right there you’ve got an incredible basis for “Tier 3”, because you’ve got Tier 1 being the article, and very necessary proving of the ownership of that article – the song by the artist – in a way that is [an] obvious way to not have that become a proprietary property of a rights organization, but everybody’s property, right?

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : Now the second thing, of all the transaction history, make that everybody’s property too. So you can go find out - or you can go dig down into that blockchain and, “Yes. There’s proof. I bought that song. Therefore, I can download it again. I bought it one time. I don’t have to buy it again. Now I can just go and download it.” And the proof of that is in the blockchain. Now, Tier 3 is where it gets really interesting, because if you have Tier 1 and Tier 2, Tier 3 let’s you look at, “If these people bought it, there’s a guy over here that shares similarity to those people. He’s probably going to want to have that song too, because it’s his musical taste.” But that level is not something prescribed by Spotify, or Pandora, or whatever. It should be happening on a level that is controlled by the user. In other words, collaborative filtering, or recommendation, powered completely – in a privacy-protective way – on the user level. All of those things can happen in the future of BitTunes – in the future of BitTunes’ blockchain model. And that stuff is way, way beyond what is available now.

John : So, in Tier 3, that is where the users keep giving the “thumbs up”, and then the other people who are using the platform are able to look and see, “Oh wow! This is very popular.” Is that what you’re saying about Tier 3?

Simon : I’m trying to be, kind of, vague about Tier 3, because there’s some pretty interesting technology that I don’t really want to describe in too great of detail. But I can talk generally about it. One of the ways of thinking about it is that – and just by your question back to me, was a question saying, “Well , users are going to be able to do this, and then look to see who’s like them, and…” Actually, when you get to technology like this, there’s a concept in computer science we call “machine logic”. That is, when things happen, kind of, automatically, because you don’t really need to involve the user in a recommendation, if it has come from data that is there available, and there are parallels or synergies between those disparate elements of data that can be then mined. Now, this gets into what is called “big data”. But, you know, as soon as I hear that word “big data”, immediately in my mind it’s like, “Well, okay. Big data. Who owns it?”

John : Right. [laughter]

Simon : You see what I mean? I’m interested in big data that’s owned by the people, and giving the people tools that mine and use machine logic between each other - and their devices - that is privacy-protective, to deal with all of that big data. Because the big data belongs to them.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : You know? Now you look at Google’s business model. We’re all typing search queries into Google. Or we’re all putting our intimate lives on Facebook . Who owns that? Who owns all of the searches going into Google? I mean, Google has co-opted them. But who created them? You know, we create that stuff, and it makes a ridiculous amount of money for Facebook and Google . But it’s user data given willingly by users. So, if you look at a paradigm that is a possible future paradigm, what about when you have systems that are really independent of these great, big monopolies - like Google and Facebook – and you push the ownership of big data down to the user level, then you have created a completely new paradigm. And now there are new business models that can flourish on top of that. Because, of course, you can provide services to these people, etc. But why not give them the power to be able to have something – a device in their pocket – that is automatically giving recommendations to new songs, but that recommendation is not coming from a proprietary company that’s got them paying 30 euros a month, or 30 dollars a month, just to subscribe?

John : Right. You’re saying that information – that recommendation – is coming from the other users.

Simon : Yeah. [It’s] coming from the other users, and powered by a global P2P system, powered by all the devices networking with each other. Why not? Absolutely, completely possible. But what company – what big company – wants to actually make themselves irrelevant, by instituting a system like this? Google is not going to do it. Facebook is not going to do it. Okay?

John : No. So if I’m one of the people using BitTunes down the road – let’s say five years from now – and I recommend, or I give the “thumbs up” to a song – basically, I just put it out there that I like this song – do I get anything in return for saying that I like that song?

Simon : In a system like this, because it’s privacy-protective, you wouldn’t even need to say, “I like that song.” The fact that you like that song just means that you’re part of a club, in a sense, of people who are – I can see no reason why they wouldn’t be willing to be part of that system, because the quid pro quo, if you like, or the benefit of it is, if you’re sharing things you like, then other people are benefiting from knowing the things that you like, and you’re benefiting from knowing the things that they like. Therefore, in an environment like that, you’ve got something that’s akin to, kind of, natural selection. Because you’ve got new memes and new things that will pop up, and suddenly become popular, and that will spread virally, just like things like this do. But, it’s like the commons. It’s the benefit of all being involved in something, and all benefiting from it.

John : Right. So you’re saying that just my listening to the song is an indication that I’m giving a “thumbs

up” to the song – that I like the song.

Simon : Yeah. If you’re playing that song around and around, if this was in another platform – let’s just hypothetically talk about videos. Maybe you’re playing a video around and around, but the video is a little bit – how we say, “adult rated” maybe, [laughter], or if you know what I mean?

John : Sure. Sure. Yeah.

Simon : You know, content is personal. Right? Whether it’s music, or whether it’s – I mean, someone can be, like that band “Niggers With Attitude”, or whatever. It’s like there are a lot of swear words, and there’s a lot of this and that. It’s personal.

John : Sure.

Simon : I mean, the fact that I’m listening to that around and around, maybe I don’t want everyone to know that. Or maybe I’m watching a video, and maybe it’s political, too. Look at Iran. Look at countries around the world where what you listen to, or what you watch, is a matter of life and death. It can get you into a lot of trouble.

John : : Right.

Simon : So, these things are personal, and there are big implications. In the West, we take these things for granted, but what I Iisten to, and what I consume should essentially be private. And there’s a great way for having this. If you make an architecture that, by default, keeps it all private, but exchanges that information – that big data – on a safe level between users, and then that whole system just helps it users see what’s trending, or what’s popular or what’s not – but without identifying any particular user. In other words, I could say that [with] a model like this, the entity that’s controlling it – because there has to be some sort of organization behind it that’s facilitating it. We want to know what you’re interested in, but we don’t care who you are.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : We don’t want to know who you are. We just want to know what you’re interested in, so it can be part of a system that can help educate other people about things that are trending.

John : I love the whole idea. And you know, someone might think, “Hey. Okay, well you get this thing up and running, and we like you, we know you’re a nice guy, you’ve got integrity. But what’s going to stop Google, or Mark Zuckerberg, from buying this from you, and then making sure that they can figure out who’s watching what, and listening to what?” How do we know that - since this is basically something that your company would own, and is therefore centralized – how can we be certain that it’s not just going to get sold down the river?

Simon : I’ve been very, very aware of exactly that issue right from the beginning. And that is that it’s all about who I am, and who we are as a company, and what’s our end aim. And I can just say - right from the beginning - that idea of doing a trade sale, to any large company, to me is just out of the question for something like this. You cannot sell your soul. You can’t build up this thing into a great, big phenomenon, and then go sell it to Google. No matter how many, bloody, billions and billions and billions of dollars they offer. So…

John : Now wait, you’re telling me that if Mark Zuckerberg, today, offered you $5 billion…

Simon : I wouldn’t take it.

John : … Plus the five prettiest Chinese women, and Mexican women - that he could get a hold of- you’re telling me…

Simon : No. no.

John : … and that might be a Zuckerberg trait – I don’t know the guy that well, but he seems a little whacked to me – but are you telling me that you wouldn’t take that?

Simon : No. I would take it. I would not take it. But the reason is, by the way, because there is another alternative, and that’s called a “people’s IPO”. You know, to save it for the IPO, and then let it float. But also, make it float on the stock exchange in such a way that no corporation can ever own more than 10%.

John : Nice. I love it.

Simon : Okay? So, therefore, the people will buy in, but Mark Zuckerberg – in the articles of incorporation of the company – no corporation, like Google or Facebook, could ever own more than 10% of the company. So they never could have a controlling interest.

John : I like it. Can you get more specific in the articles, and say, “And specifically, Mark Zuckerberg cannot even own 1%”. Can you do that? Because the guy has too much already. I mean, come on.

Simon : Well exactly. This is one of the great problems of capitalism, too. Isn’t it obvious? I mean, doesn’t everybody realize this? This endless growth mentality that feeds capitalism. I mean, what is the point? What is the point? How many trillions, or billions, do you need to have to feel secure. I mean, enough is enough, you know?

John : The counter-argument to that is, kind of, a “Randian” – by that, I mean Ayn Rand. Not my favourite person in the world. But the counter to that is like, “Who are you to say that there should be a cap on what anybody makes? Shouldn’t anybody be allowed to make absolutely as much as they want to, from now until the end of time? ” And I counter that with, “Well, the only problem with that is usually those people who are doing that are stepping on people, and hurting people – whether it’s the environment, or people, or whatever .” They’re almost always – when they get up to making billions and billions – they’re almost always doing something, if it’s not blatantly nefarious, it’s something that a massive group of people disapprove of.

Simon : Oh, yeah.

John : For instance, I am among one of millions people – tens of millions of people – who understands what Facebook is really doing. The majority of cattle – you know, the “sheeple”, they really don’t have any idea what the business model of Facebook is. That is, “Gather all of this free information from all of these suckers, and sell it off to the highest bidder.” And when you take that kind of model – and I don’t know where else he’s selling it. I don’t know who else he might be corroborating with, in terms of governments, or what-have-you. Right? I mean, we don’t know that, but…

Simon : We do actually. [laughter] We do.

John : Oh, we do?

Simon : We do. Yeah, we do know that they’re doing that, and it’s wrong. But getting back to the monetary side of things, someone said recently – I think it was a Davos – they said that, “It’s now half the world’s wealth is owned by 1% of the population.” Or something. It’s just wrong. And you only have to look at the pressure being put – austerity measures in Europe, etc.

John : Greece, yeah.

Simon : Yeah, and Greece. I mean, it’s like the fact is that all of the money that Greece borrowed - that got them into so much trouble – where did that all end up? It ended up in the pockets of the oligarchs, and the corrupt government officials, etc. But it’s the people that end up having to carry the can.

John : That’s right.

Simon : And so, there’s a lot of iniquity. My background is – and [to] a lot of people in the U.S. this might sound crazy – but my grandmother was a communist. I come from a very left-wing family. And let me say, she’s actually a middle-class girl. She grew up in a very middle-class family, but she reacted to that [and] joined the communist party. But this was in Melbourne, in Australia, in the 1920s. She didn’t know what communism was, but she just was reacting against the hypocrisy she saw in the wealthy classes. She had servants in her house when she was a child. This is my grandmother. So I came from a very left-wing family. My parents were left-leaning people as well. I’ll tell you, as an adult, my battle for the last 30 years is actually feeling okay about being a businessman, because that was almost a dirty word in my family. I come from a background that is very social action oriented, and very toward empowering the people. I’ve had to find that middle-ground which is, “What can I do in life that I can make money, and feed my family, etc. and have reasonable life. But at the same time not go against the principles of the heritage of my family, which is all about the greater good.” And not just becoming richer and richer and richer. I mean, I think if I make a few million in my life, do I need to have 10 million, or 20 million, or 100 million? I don’t think so. The people who feel like that, they must be incredibly insecure. I think you’re put on the planet to do certain things. For me it’s about, there’s a lot of iniquity at the moment, and there are very few people who are really, seriously taking on the challenge of trying to work out how to make more equitable systems. And at the moment, BitTunes is, like I said, the molecule on the back of a flea, on the back of an elephant. We’re nothing. But the users who are there - who do understand the principles on which we’re founded, and where we’re planning to go - they’re very enthusiastic, because they know our heart’s in the right place, and our intentions are good. And as we grow, we’ll find backers, and venture capitalists who resonate with our model.

John : Yes.

Simon : Like I said, you don’t have to have a trade sale to have an exit. You can have a public exit in such a way as I’m describing, and those VCs can still make huge multiples on their investment. But the end game is something that makes much more sense, which is, get there by empowering people, rather than ripping them off.

John : I agree Simon. Very well spoken, sir. Very commendable. So tell us a little more about BitTunes. How many people do you have on your team, and what do you see as the future, coming up over the next, let’s say, five year period of time for BitTunes.

Simon : Okay. So we’ve got about three developers on our team, and a couple of business and coordination people. We’re very much bootstrapping at the moment. I’ve got something like $150,000 Australian into this project, out of my own money, since the beginning. That’s why BitTunes exists. We’ve had approaches from different people about how to finance BitTunes, and a lot of those were alt-coin kind of players, wanting us to be a BitTunesCoin, and blah…blah. I mean, which I completely resisted, because those models are very [sus(pect)?]. So, I’ve been holding out for doing it the proper way. I think what we’re doing at the moment is actually what we call a “minimum viable product”, which proves the principle, and shows what BitTunes can be, and it’s gathering momentum. But the next step is really about scaling up to a Tier 1 – kind of, what we were talking about, Tier 1 and Tier 2 – which is like a blockchain implementation for song rights and ownership, and then mapping and recording transaction histories. Then we’ve got a whole lot of other technology about a recommendation, which I have been describing before, which we just can’t wait to put on top of this. But one of the things about being a startup is that you’ve got to walk before you can run. If you try to and go too fast - if you try and go ahead of yourself – you’ll get burned, and you’ll go down in flames. You just have to know your limits, and you have to just go as and when. Luckily, we’ve got a great team of people who make big sacrifices in terms of wages, etc. to just keep on maintaining the system as it is. And we’re out there talking to people at the moment about helping us finance the next level. You’ve got to find the right backers. There are people who will understand where we’re coming from, [and] who will resonate and support us. That’s one of the reasons why I’m moving to London, and most of the team will be moving there. Because one of the comments we get from investors who we’re talking to is – and I quote – “It’s a pity you’re in Australia.”

John : “Hey, what are you doing out in the bush?”

Simon : “What are you doing around the wrong side of the planet? Nothing’s ever going to happen down there.” It’s just sad, but it’s true. Even living in Sydney, you’re provincial, compared to London or Silicone Valley. You just won’t bump into the people who can help you.

John : No, that’s really true.

Simon : Simple as that.

John : Okay, so Simon, if you would, walk us through BitTunes. Where do we start? From the time that we upload a tune, can you walk us through it?

Simon : When you upload a song to BitTunes the song is available everywhere on the planet. There is no boundary. One of the things about music systems around the planet [is] they’re very much tied to right and royalties regimes. We use a “creative commons” license, and we just basically check that every song – if the writer, or owner, of that song has uploaded it to BitTunes – then we can use the creative commons license to make that song available to be purchased anywhere. Whether it’s Russia, or China, or North Korea, or – it doesn’t matter. As long as that person has Bitcoin, they can buy that song, because there is no rights regime saying, “It can be sold in Singapore, but it can’t be sold in Malaysia. It can be sold in Thailand, but not in Burma.” Now Bitcoin is very young. Bitcoin is at the very beginning, but it will grow. Now, the other way of looking at this is a simple understanding of demand and supply. There is 21 million Bitcoins ever going to be available, okay? At the moment there is like 12 million in circulation, or whatever. They’ve lost about a million of them. If everyone in Australia – there’s around 21 million people in Australia – if everyone had one Bitcoin, that’s all of them gone. Well, there are 6 billion people in the world. It doesn’t take a genius to work out that, over time, those 21 million Bitcoins are going to get divided among many more than 21 million people.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : It’s going to be maybe hundreds of millions of people that will have Bitcoin. That means that those little Satoshis, or those little tiny percentages of Bitcoin that you might be earning from trading your song in BitTunes, now at current exchange rate is very small. But those little percentages that you’re earning now, [if you] keep them inside your royalty wallet inside BitTunes, and don’t trade them out, because in 3-5 years you can be sitting on a nice little nest egg.

John : Yeah.

Simon : Now, I’m not one of those people that says, “To the moon! Bitcoin is going to be worth $10,000.” I don’t want to second-guess the value, but it doesn’t take a genius to work out [that] you’ve got a finite supply, and you’ve got something which the U.S. government can’t just print billions of new Bitcoins every month because they want to feed the money supply. It’s not going to happen. This is the opposite. But like everything, when you’re young you don’t really have the benefit of having seen things go for years, the twists and turns of the way history evolves. But I can tell you, I remember the 1980s. There were no mobile phones. I had an analogue, reel-to-reel tape recorder. Digital “anything” didn’t exist. We had to go from reel-to-reel tape recorder to a cassette to make a dub of a song. And when we did we lost fidelity, you know? I remember when digital came in, it was a revolution. Then I remember when the web came in. These things didn’t happen overnight. They each took, five, ten, fifteen years. So let’s just keep it in proportion. Bitcoin has only really hit the mainstream in the last year or two. That’s just a second, you know?

John : Right.

Simon : So time will go by anyway, and over 3-5 years the world is going to change a lot, and at some point Bitcoin will become very valuable. So I’d rather be earning my royalties in Bitcoin, in a world where everybody can buy it, from any country, without any limitation, and to get in on the ground floor, so that you’re one of the early people. Because as more and more people discover BitTunes, we don’t have the kind of catalogue that’s available in Spotify, etc. But when you put your song into Spotify, you’re going to get lost in the noise. You put your song into BitTunes, you have a very, very high chance of being discovered.

John : Because there are very few people starting out.

Simon : Yeah. As soon as people buy that song, the people who previously bought it get rewarded in small payments, because they are providing the song to the new requesting user. And so BitTunes, by the way, is not just about song trading. There’s communication features in BitTunes. People can make offers and requests, and there’s a kind of Twitter-like stream where you can communicate to other musicians. You can communicate directly to your fans, if you’re a band. And if you’re a fan, you can communicate directly to the musicians. All of those social features will just keep growing and growing. What happens with BitTunes is, when somebody buys a song the algorithm in BitTunes will immediately look for five previous buyers of the song, to provide parts of that song to the new requesting buyer. And the way in which those five are selected depends on various circumstances. At the moment, in BitTunes , it’s very likely that you will be selected because there are not that many users. Over time, the algorithm is weighted towards, the more you are a good citizen inside of BitTunes – in other words, if you’re logging on every day, and if you’re rating songs, and doing things, and being part of the ecosystem – you’re therefore more likely to be chosen as one of the five providers of the song to the new requesting user. We’re tweaking this all the time, but what it means is we’re trying to find a way that rewards good citizenship in this ecosystem. At the moment, there are two levels of cost – or price – of songs in the system. If songs are on our Top 100s they’re valued at $1 U.S. dollar, and if songs are outside the Top 100s they are 50 cents. Why we use U.S. dollars as an indicator of value is that people are very familiar with that. If I try to give that price in Bitcoin, people would go, “What is 0.016951 Bitcoin?” Right? We show both together. But what that means is that the primary currency of BitTunes is Bitcoin. So it’s floating up and down all the time. And whenever a song is purchased, we pin the exchange rate of Bitcoin, and we measure the exact exchange rate at that exact moment. So for people, when they say, for instance, put $10 U.S. dollars into their trading account in BitTunes, they might notice that that goes up and down with the price of Bitcoin.

John : Mmm Hmm.

Simon : So Bitcoin goes down lower, [and] suddenly they’ve got eight dollars in there instead of ten. They buy a few songs, and it goes down, but then Bitcoin starts to rise, and all of a sudden they’ve got $15 in there, and they [say], “How did that happen?” Because our primary currency is Bitcoin. Okay, so the percentage goes like this. If it’s in the Top 100 and song is priced at $1.40, cents of that song goes immediately to the artist – as the copyright owner. And the other 40 cents is split amongst the people who are providing the song to the requesting user. And BitTunes takes 20%, which is 20 cents out of the dollar. But the interesting thing about this is that what’s happened in BitTunes lately is, as more and more songs have gone into the system, many of the songs in the system now are not priced at $1. They’re priced at 50 cents. When a song is valued at 50 cents, half of that goes to the artist, and the other half is divided amongst the users. So, what will happen over time is the vast majority of songs on the BitTunes network will be at 50 cents. But as they get more popular, they rise up, they rise up, and then when they get into a Top 100 they double in price. So therefore, the idea is, buy early – buy when it’s 50 cents, when you think it’s going to be a good song – tell your friends about it, it goes up… it goes up. Then it goes to a dollar, and then more people buy it, because they say, “Ah! This is a popular song. It’s going to get more popular.” But us, as a company, we take only when it gets on the Top 100. So therefore, we’re not interested in what we call “the long tail of music”, where things are valued at 50 cents. We take it at the valuable end of the “long tail”, because we’re providing a service to feature those songs on the Top 100s.

John : Okay. So the artists putting their music out there, they’re going to get paid whenever it’s downloaded.

Simon : Instantly.

John : And if I download a song on there, am I always going to get paid a little something?

Simon : Not always, no. It depends on various factors. Early in the system you’re very likely to get paid often, because the system always looks for five providers of the song to provide to the new requesting user. As the system gets larger, and larger, and larger, that “good citizen algorithm”, if you like, is more and more important, because the system will be looking for five users all the time, for every time it wants to provide a song. It will not choose the same five users every time. It will choose a different five users. But the basis on which ones are chosen – we’ve worked a lot on this problem, which is how to choose those users – if it was completely flat, and the distribution fanned out, then no one would make any money, because everyone would have the same likelihood of being chosen. So therefore, the system sounds fair, but the system wouldn’t work, because no one would ever experience making a profit on a song. So you’ve got to weight it in some way, so that there are weighting mechanisms that give a weighting to certain behaviour. Because then - like if you’re not an active user, and you’re not writing songs, and you’re not returning very often - well, chances are that you’re not going to get chosen that often. If you are, you will. But then what we’ve done is also create a system. When we choose five users – because we have a probability index that helps choose the most likely users to be chosen. But then of the five users that are chosen, we automatically choose two from “newbies” – people who have just entered the system – to give them some encouragement. So we’ve thought very hard on trying to make a system that is as fair as possible. It rewards good behaviour in the system, but also gives some incentive to people who have just entered the system and haven’t managed to develop that kind of reputation behaviour yet.

John : Man, I love it! This is cool. Now, when can I start using this? I got an email from someone that works for you, who is in China, I believe, right?

Simon : Yeah, That’s right.

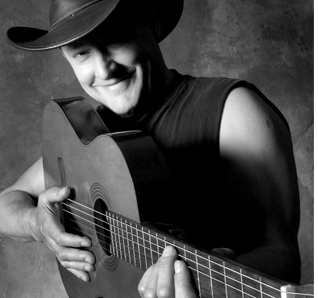

John : She sent me an email that said, “Your song” – which is “Ode To Satoshi” – “Your song is now available on BitTunes.” Is that right?

Simon : Yeah. It’s right there. You go into “New Songs” on BitTunes, and it’s sitting on top.

John : Okay. I love that, man. So I can start earning money from my…

Simon : You have already, by the way. I saw somebody purchased that song just the other day. So you’ve got some royalties sitting in your account.

John : Oh, wow! That’s great. So I should put a call out, “Listeners worldwide. Go to BitTunes immediately and download “Ode To Satoshi”, the official Bitcoin song. Do that now.”

Simon : Yeah. That’s right.

John : Wow! That’s exciting, man. So now what do I do from here? Is there a wallet that collects my royalties for me? Can I take the Bitcoin? Can I take the Satoshis and the Bitcoins? Can I take those away out of that wallet anytime I want to?

Simon : You can indeed. You can transfer them out. But my advice is not to, because one of the things [is] the Bitcoin network, kind of, punishes small transfers. If you’re transferring $10 million, the transfer fee is insignificant. But if you’re transferred 5 cents, or 20 cents, you’re going to have a little transfer fee, and it takes a while to get through the network. So it’s, kind of, smarter to leave your royalties in your royalty account. If you go to http://www.bittunes.com/ , and just look at the web page, on the very top you see a graphic that shows the transaction page inside BitTunes. And you’ll see an “earning account” and “deposit account”. Your deposit account is where you put your money in, and your earning account shows the royalties you’ve been earning. Recently my deposit account went down to, kind of, zero – because I spent the Bitcoins – but then my earnings account had $5 US dollars in it, from all of the royalties that I’ve been earning. So I just transferred that $5 US dollars back into my own trading account, so I could buy more songs. So that’s the way BitTunes works.

John : Okay. So somebody can go, right now, and download the BitTunes app onto their Android phone? Is it also available on iPhones?

Simon : Apple is a bit of a problem…

John : Well we know that. [laughter]

Simon : Yeah, for two reasons. First of all, they didn’t want to let any Bitcoin apps on the “App Store”. But then they had let a few in. Then we started to notice that they’re pulling lots of legitimate music applications out of the App Store as well, because they don’t want competition for their own music applications.

John : All I have to say to Apple is, “You dirty rats, you.” But okay, so let’s see. Someone downloads the app onto their Android phone – which, if you don’t have an Android phone, folks – listen, turn in your iPhone right now and get an Android phone. It’s a superior phone in many ways. I recommend the “Galaxy S5”. The camera alone is a good reason to go from the iPhone. So then they can go to the Google Playstore, and they can download the app?

Simon : We’re still officially in our beta program. So simple, if you go to the BitTunes web site, there’s a link right on the front page, it’s just, “Join the Community”. So go to the BitTunes page, join the community, and once you apply to join the community then you can go to the Play Store through that link. The way Google runs this is there are a few little hurdles to jump over. That is, when you go to the community, you’ve got to use the same browser that you tend to use with your Gmail. Then that will tell Google that you are “this person”. Then when you go through our community – because that will take you to the App Store, but it’s like a little “chapter” of the App Store, that is authorized through the beta community. And then you can just download the BitTunes app, and away you go.

John : Nice. Wow, that is easy. So BitTunes.com is where people can go. Can you also tell our listeners other ways that they can get in touch with you?

Simon : There’s BitTunes.com, which is basically just, kind of, what we call a “brochure site”. It’s not really an interactive site, but it will be. It will be where all the Top 100s will be displayed. More information about BitTunes on http://www.bittunes.org/ , which has got deeper information about the philosophy, and the history, and how the project came about. But I think one of the best ways – even if you don’t have the Android app, and are unable to download it – still join the community, because you’ll see the chitter-chatter by all of the users, and the issues that come are coming up, and discussions about what we’re doing, etc.

John : All right. Well, listeners, we’ve been listening to Simon Edhouse from Adelaide, Australia. Simon is the CEO of BitTunes, creating a people-powered platform to reinvent global music distribution. This charge is being led by Simon Edhouse. Simon, thank you so much for being on the show.

Simon : Thank you. I’ve really enjoyed it. It’s been great.

John : Good. And let me ask you, before we go, what’s the weather like there in Adelaide?

Simon : Oh, man. It’s like 35 degree today, which is somewhere around 100 fahrenheit, in U.S. terms. So yeah, it’s stinking hot outside.

John : So it’s almost 8:30 pm here is Nashville. What time is it there in Adelaide?

Simon : It’s just 12:51, almost 1:00 in the afternoon, and it’s like, “Don’t go outside. It’s too hot.”

John : [laughter]. Wow. What I don’t understand about the time change thing is that there is that 30 minutes – I’ve never seen that before – there’s that odd 30 minutes there.

Simon : Oh yeah. But it’s just the same as New York. Like, between New York and California you have a few hours, right?

John : We’ve got a few hours, but we don’t have half-hours.

Simon : Oh, okay. Yeah, we divide it. We’ve got “eastern time”, and then we’ve got “central time”, and then we’ve got “western time”. Western time is Perth, central time is Adelaide and Darwin, and then eastern time is Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane. But the other thing, by the way, is [that] here it’s Tuesday.

John : Ah. Okay.

Simon : You’re still in Monday.

John : Still in Monday, man.

Simon : Yeah. We’re on Tuesday already. The “International Date Line” is in the middle of the Pacific, so the day starts in the middle of the Pacific, goes around the world, and eventually comes around. I think Americans hate that, that you get the day at the end of …

John : Oh, no. I think the only reason Americans don’t like it is because Australia is ahead of us in something.

Simon : [laughter] That’s funny. We don’t like it because the New Zealanders are slightly ahead of us.

John : Oh no! Not those guys. [laughter] All right, hey Simon, thank you so much for being on the show, and I would love to have you back on here in a couple of months – maybe six months – and we can find out an update about BitTunes. BitTunes is very exciting stuff, man.

Simon : Yeah. We’ll be launching a really interesting project soon, but I can’t talk about it just yet. But [sometime] in the next few months, I’ll let you know.

John : Yeah. Please keep me informed.

Simon : Okay. Thanks so much. Cheers.

John : Cheers. Thanks Simon. Bye.

Simon : Bye.

[Segway music]

John : I know that it may sound absurd, but I have for you a magic word. And today, the magic word is “tunes” : T – U – N – E – S. As in the sentence, “I am so excited about BitTunes, and how it is reinventing global music distribution by creating a people-powered platform”

[music and lyrics to “Ode to Satoshi” song]

John Barrett : Now climb aboard y’all! This train is bound for glory… and there’s plenty of room for all…

“Well Satoshi Nakamoto, that's a name I love to say,

And we don't know much about him, but he came to save the day.

When he wrote about the way things are,

And the way things ought to be,

He gave us all a protocol this world had never seen.

Oh Bitcoin! As you're going into the old Blockchain,

Oh Bitcoin! I know you're going to reign, gonna’ reign,

Till everybody knows, everybody knows,

Till everybody knows your name.

[guitar instrumental]

Down the road it will be told about the Death of Old Mt. Gox,

About traders trading alter coins, and miners mining blocks.

But them good old boys back in Illinois,

And on down through Tennessee,

See they don't care to be a millionaire,

They're just wanting to be free.

Oh Bitcoin! As you're going into the old Blockchain,

Oh Bitcoin! I know you're going to reign, gonna’ reign,

Till everybody knows, everybody knows,

Till everybody knows your name.

[instrumental interlude]

From the ghettos of Calcutta, to the halls of Parliament,

While the bankers count our money out for every government.

Oh, Bitcoin flies on through the skies of virtuality,

A promise to deliver us from age-old tyranny.

Oh Bitcoin! As you're going into the old Blockchain,

Oh Bitcoin! I know you're going to reign, gonna’ reign,

Till everybody knows, everybody knows,

Till everybody knows your name.

Till everybody knows, everybody knows,

Till everybody knows your -- "Give me some Exposure" --

Everybody knows your name.

Singing,

Oh Lord, pass me some more,

Oh Lord, before I have to go.

Oh Lord, pass me some more,

Oh Lord . . . before I have to . . .

Go . . .

[instrumental finale]

[applause]

John : Oh-ho! Thank you East Nashville! Y’all be good to each other out there, ya’ hear?

[Segway music]

John : I’d like to thank my guest on the show today, Simon Edhouse, the CEO of BitTunes. BitTunes is not just about making money, folks. It’s about doing what’s right for humanity. In the end, it makes so much more sense to get there by empowering people, rather than ripping them off. Simon, we are glad that you are at the helm of BitTunes, and we are behind you 150%. You can find more information about BitTunes in the show notes.

And I’d like to give a “thank you” to Maria Jones at CoinTelegraph (http://cointelegraph.com/ ). Maria, thank you so much for getting me my tickets. And, thank you very much, Mr. and Mrs. Snow, for your generous offer, and thank you for your generous offer as well, Mr. Malone. I will see you guys in Texas, here at the end of March. The “Texas Bitcoin Conference” is, in my opinion, the best Bitcoin conference in North America each year, and I’m really looking forward to meeting a lot of new people, having some good food, a couple of cold beers, and maybe getting a chance to play “Ode To Satoshi” for everyone. Austin, Texas – here I come!

If you’ve enjoyed the show today, please take a minute to leave a comment on Let’s Talk Bitcoin, in the comments section, right there below the show notes :

https://letstalkbitcoin.com/blog/post/episode-55-bittunes-setting-music-free

You can also leave a message on Soundcloud :

https://soundcloud.com/bitcoins-and-gravy/episode-55-bittunes-setting-music-free

or do the old fashioned thing and send me an email.

And, of course, Bitcoin and Litecoin tips are always appreciated by the hardworking writers and podcasters in the Bitcoin world. Many of work as volunteers, and sure could use those tips.

Signing off now from East Nashville, Tennessee. I’m your host John Barrett, with my trusty companion Maxwell by my side. Say goodbye Maxwell.

Maxwell : Grrrr…..

John : Y’all be good to each other out there now. And remember, the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men and women to do nothing.

[show outro music]

Maxwell : Grrrr…..